Global Dialogue Briefing on the Responsible Diffusion of Open AI

-

Event

-

AI Governance

-

Multilateralism

The first UN Global Dialogue on AI Governance will take place in the margins of the AI for Good Summit in July 2026 in Geneva. In the lead up the Simon Institute for Longterm Governance is hosting a briefing series for diplomats and multistakeholders together with the Permanent Missions of Singapore, Kenya, and Norway. The briefings are deep dives on potentially promising focus areas within the seven high-level discussion topics (4a-4g) that member states have agreed to address in the Dialogue.

The first briefing on January 27 focused on the responsible diffusion of open AI models, which sits at the intersection of “4a) The development of safe, secure and trustworthy artificial intelligence systems” and “4g) The development of open-source software, open data and open artificial intelligence models”.

The event featured welcome remarks from H.E. Mr. Jaya Ratnam (Singapore) on behalf of the co-hosts, a message from the co-chairs of the Global Dialogue, H.E. Ms. Egriselda López (El Salvador) and H.E. Mr. Rein Tammsaar (Estonia), as well as an introductory presentation from Maxime Stauffer and Renata Dwan (both Simon Institute). Subsequently, Stephen Casper (MIT), a leading expert on open-weight AI model risk management, explained the technical challenges of the field and highlighted potential governance implications.

Why open-weight risk management matters

Open AI models have a range of benefits (see SI explainer Part I). Most notably, if a user can download an AI model and run it on local hardware, this limits the dependency on the AI model provider. Sensitive business data or government data can remain local. Furthermore, open AI models can be fine-tuned with additional data to fit specific needs.

Unfortunately, the same local autonomy provided by open AI that limits extreme power concentration does have a flipside: it increases misuse risk.

a) Open-weight AI risk management is hard

First, for closed AI models, AI companies deploy filters on the input messages from the user to the model, and on the output that the model creates before it is sent to the user. These safety filters are external to the AI model and trivially easy to disable for downloadable AI models.

Second, AI companies train their AI models with reinforcement learning from human feedback to refuse harmful requests. Unfortunately, only a small amount of fine-tuning is sufficient to remove these refusals again on open models. Similarly, fine-tuning makes it possible to introduce new dangerous capabilities to models. The costs of this fine-tuning are very limited, amounting to less than $0.20 for GPT-3.5.

Hugging Face is the most popular AI model hub, hosting more than 100’000 AI models. As Casper pointed out there are more than 7’000 AI models that have “uncensored” or “abliterated” in their names on Hugging Face alone. This indicates that these are versions of open AI models that have been specifically fine-tuned to make them less likely to refuse requests.

Third, producers of open weight AI models are unable to monitor model usage and unable to revoke model access in case of misuse. Similarly, there may be circumstances when an AI producer might want to roll back an AI model, such as when OpenAI rolled back GPT-4o due to excessive sycophancy. This too, is very difficult if anyone can download the AI model.

Overall, there is a “safety gap” between open and closed models for misuse risks.

b) Open AI models will have dangerous capabilities soon

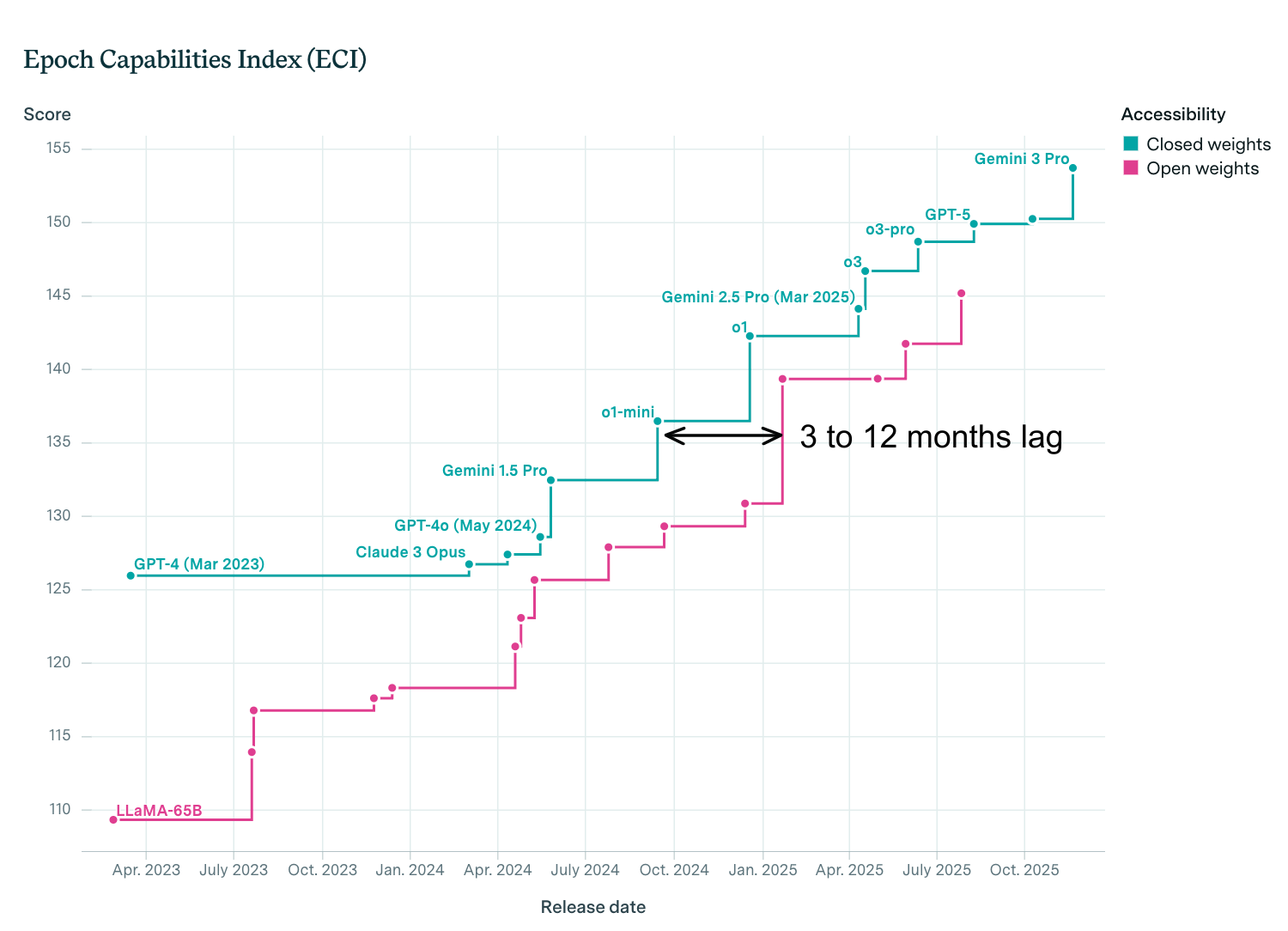

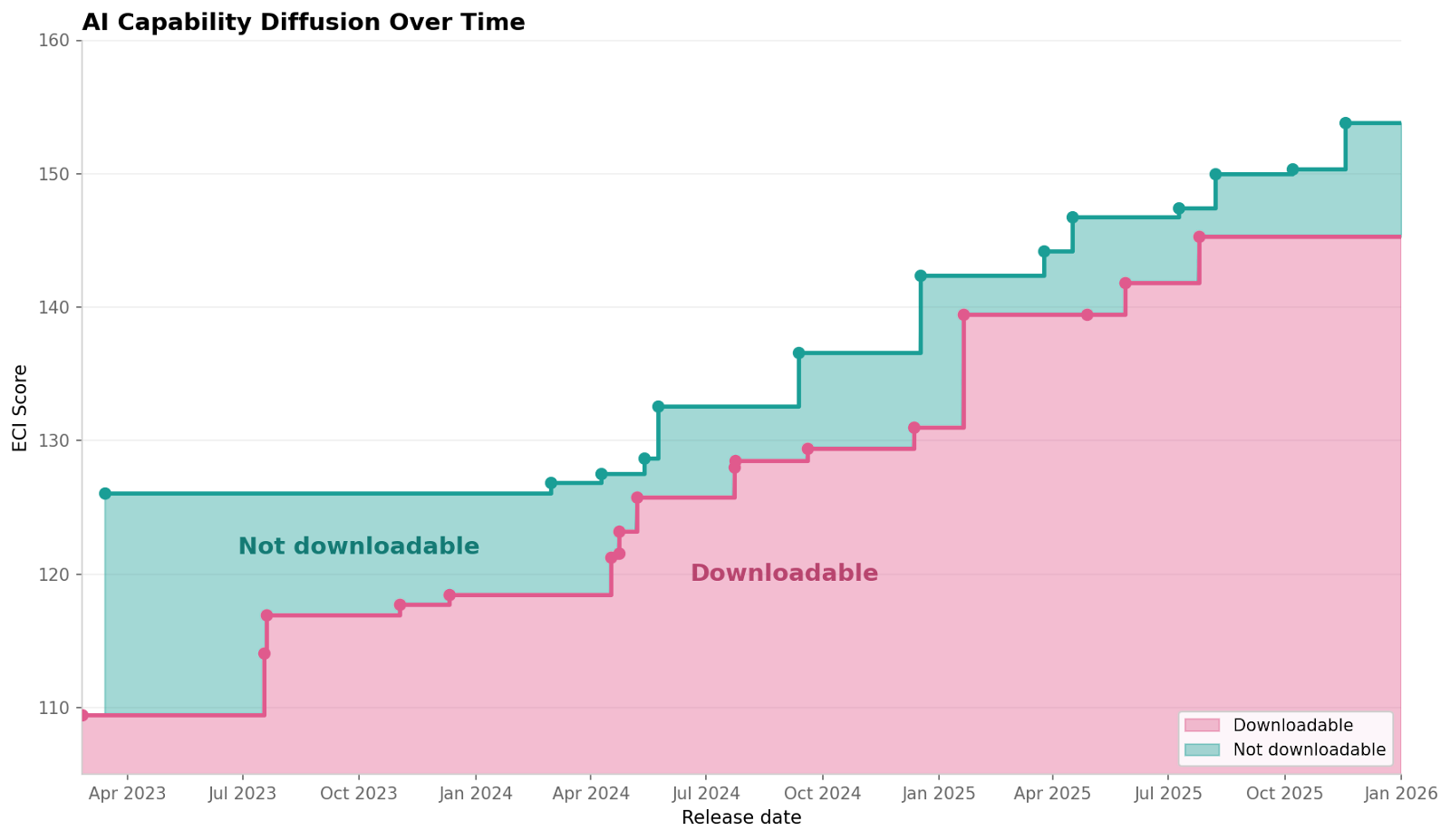

Historically, the capabilities of open AI models have trailed the capabilities of closed models by about 3 to 12 months.

That means that even though the best performing AI model at any point is likely to be closed, over time the level of absolute capabilities that are available for download with open weights steadily increases.

It also means that when closed models reach a dangerous capability threshold this provides an early warning for capabilities that may soon emerge in open models. In 2025 both Anthropic and OpenAI reported that their most advanced closed models have started to reach dangerous capability thresholds for biosecurity. Similar thresholds may soon be reached for cybersecurity.

Consequently, it is likely that dangerous capabilities in these categories will emerge in open models in 2026. On top of that, there are already many examples of current misuse of open AI models. Stephen Casper particularly highlighted the rise in AI-generated child sexual abuse material (CSAM) and AI-generated nonconsensual intimate images.

c) Open-weight risk mitigations

There are fundamental limitations for safeguarding open-weight models. Still, Casper highlighted some of the most promising approaches to ensure model safety:

Data filtering: Researchers have explored different ways to make it harder to remove safeguards from open models with very little fine-tuning. The most promising direction so far is filtering the pre-training data for problematic content. This approach, also called “deep ignorance”, means that rather than training an AI model to refuse problematic requests, the AI model never learns the knowledge needed to perform problematic requests.

Tamper-resistant “unlearning” algorithms: Some training algorithms are designed to remove or “unlearn” harmful capabilities from a model. Some methods have been used to make these algorithms resist fine-tuning or other forms of tampering that attempt to “re-learn” the unlearned information. However, the effectiveness of these algorithms is currently limited.

Transparency from model producers: Many popular open-weight AI developers have limited reporting on risks and mitigations in model technical reports.

Testing under malicious fine-tuning: Current efforts to test the safety of AI models before their release do not include audits of training datasets. Nor do they usually assess how much malicious fine-tuning is necessary to remove safeguards or add dangerous capabilities. OpenAI conducted the latter before releasing their open-weight AI model.

Model provenance: Embedding watermarks in AI models so that they can be more easily identified “in the wild.” These techniques may help investigators answer questions such as “who downloaded this model?” and “where was it downloaded from?” when open models are implicated in crimes or incidents. This improves ecosystem awareness.

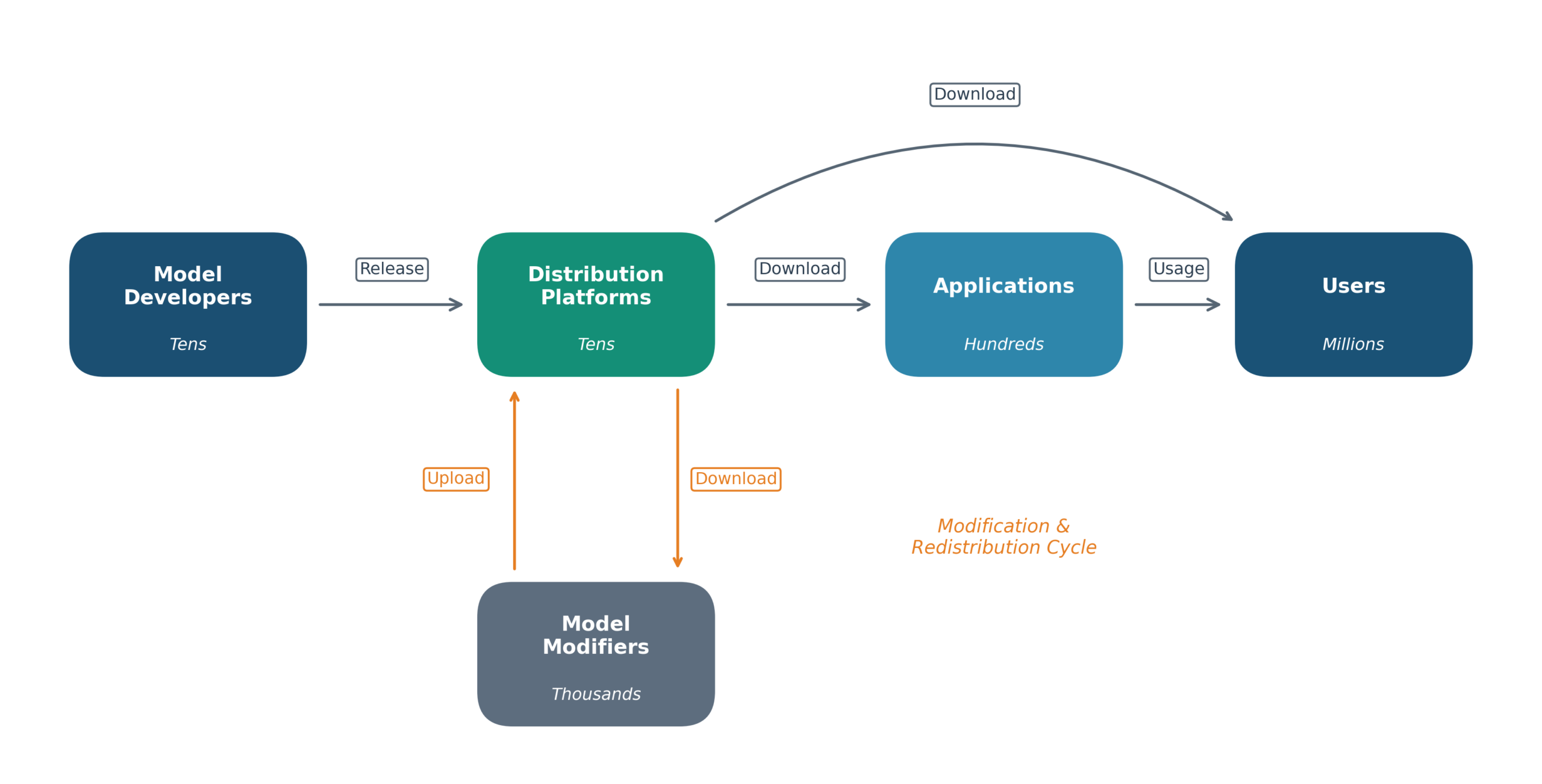

Liability: Liability currently sits mostly with individual end users. However, as a participant highlighted it may be useful to think about a control point analysis. Indeed, as Casper highlighted it is a relatively small number of open foundation models, hosted on a relatively small number of model distribution platforms, that are part of the supply chain in the majority of misuse cases. Such upstream control points would be the most effective in fighting misuse.

Why open-weight risk management is a promising topic for the Global Dialogue

A large number of UN member states and stakeholders have a strong commitment to open AI models in part to limit strategic dependencies (see SI explainer Part II). These actors have an interest in finding ways to make open models safe to be able to maintain the benefits of openness.

There is a near universal normative agreement that some misuse cases of open AI models should be prevented. For example, 178 UN countries, including all P5, are party to The Optional Protocol to the Convention on the Rights of the Child on the sale of children, child prostitution and child pornography.

Once released, open AI models almost inevitably diffuse across borders. So, there are spillover effects and countries have an incentive to coordinate towards potential minimum safety standards.

Countries have a unique ability to directly evaluate open AI models from other countries. Any national or private testing institute has access. This makes it easier to collaborate across borders and it is feasible for countries to “check each other’s homework” to the degree that’s useful.

The topic is well-suited for a multistakeholder approach with practical roles to play for civil society, the private sector, as well as Member States.

What could the Global Dialogue deliver on the responsible diffusion of open AI models?

The following are some exploratory questions that could be addressed in the Global Dialogue to advance international open-weight risk management:

Is there value in a shared definition of “responsible diffusion” for open AI models? Could such a definition link open AI misuse to existing treaty obligations and clarify expectations for data transparency and pre-release safety testing?

What role could multistakeholder collaboration play in advancing technical mitigations such as data filtering? Who would need to be involved?

Given that a relatively small number of model hubs host the foundation models involved in most misuse cases, are there voluntary commitments or hosting standards that could make a difference? What would make such commitments credible and effective?