Open AI Models: Key Actors and their Positions

-

Explainer

-

AI Governance

This post is the second in a series on open AI models (i.e. open-weight models, regardless of whether the model’s code or data is open). See the first piece for an introduction to key terms, drivers, and safety and governance considerations.

In this piece, we start with an overview of the key actors in the development and governance of open AI models, covering Chinese progress, US debates, and positions in Europe and Global Majority countries. Despite divergent strategies, all major players face a common tension: how to capture the benefits of openness while managing risks. We trace how this tension plays out across regions before proposing areas for further research and international policy dialogue and design.

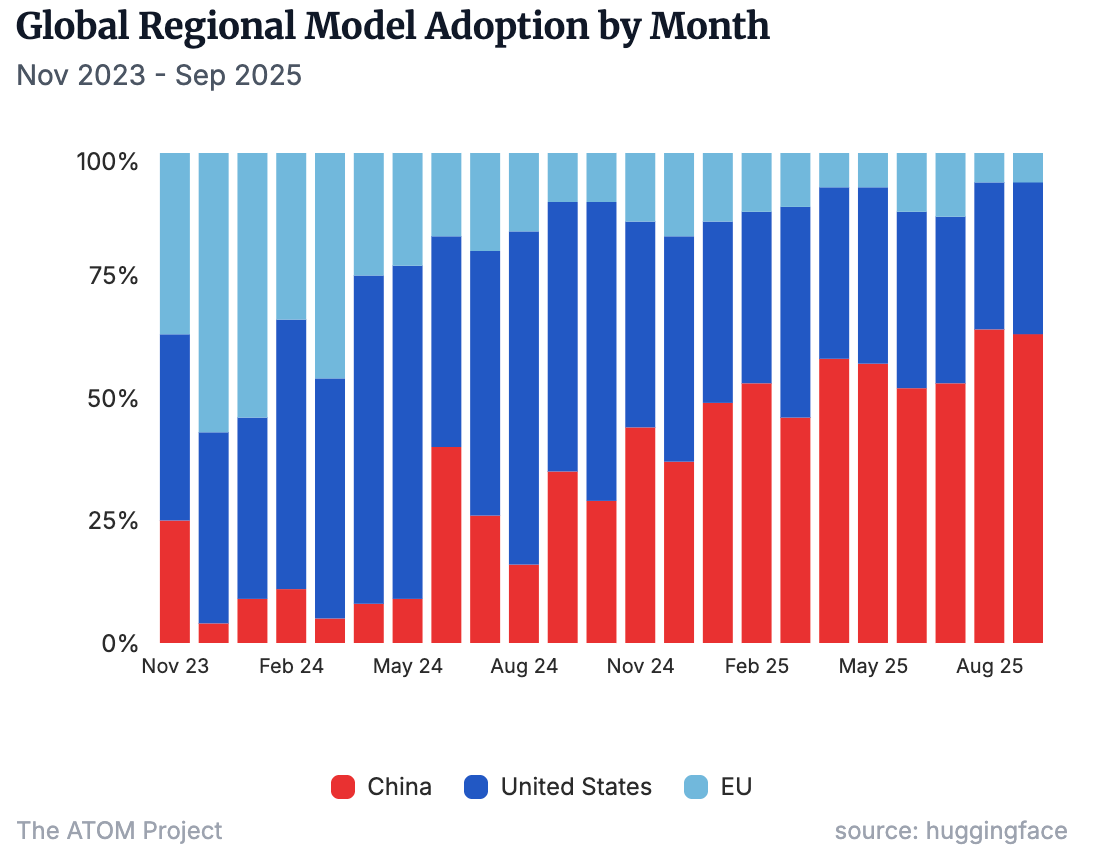

China has become a leader in open AI models

Chinese open model developers have made quick progress in capabilities and diffusion, with monthly adoption figures consistently higher than those of US counterparts since January 2025. That was the month DeepSeek made headlines with the release of its highly compute-efficient reasoning model R1. This moment in turn spurred increased commitment to open models by other Chinese developers; ByteDance is the only major Chinese AI developer to maintain a focus on closed models. Alibaba’s 300+ Qwen models now constitute the most popular open model series worldwide, with their derivatives accounting for more than 40% of the language models appearing on Hugging Face in recent months. And Chinese open model developers are not resting on their laurels. Moonshot’s upcoming K3 model is targeting an increase in effective compute of at least 10x to catch up with the world’s frontier models in pretraining performance.1

Monthly share of new finetunes and derivative models, by region of the base model’s creator.

Multiple Chinese government documents have expressed support for open-source AI.2 Among them, the August 2025 Opinions on Deeply Implementing the “Artificial Intelligence Plus” Initiative includes a call to “develop internationally influential open-source projects and development tools” and urges universities to recognize open-source contributions in student credit and faculty assessment systems. Policy support also includes an exemption from generative AI regulations for open models not offered directly to the public.

However, there are signs of growing expert and policymaker caution. China’s Safety and Governance Framework 2.0, released by a national standardization committee in September 2025, devoted more space to risks from open-source than the first version. It included a call for enhancing the “security capabilities” of the open-source innovation ecosystem.

In the US, commercial and policy interests are diverging

In the US, in contrast to China, the best-performing models are generally not open. This divergence stems from three factors: commercial pressure to recoup infrastructure investments; the diminished need to build off each other’s innovations when already at the leading edge; and heightened concerns about misuse. While Meta’s Llama series had an early global lead in performance and adoption, the company appears to have moved away from an open-first strategy. Mark Zuckerberg wrote in July 2025 that “we’ll need to be rigorous about mitigating [superintelligence safety] risks and careful about what we choose to open source”. OpenAI released two open-weight models in August 2025 in a move widely interpreted as a response to Chinese strengths in open models, but the company’s most capable models remain closed.

The US AI Action Plan released in July 2025 highlights the benefits of open-source and open-weight AI for innovation and adoption, while also recognizing their geostrategic value given their potential to become global standards in some fields. This sits within a broader view of global competition across the whole AI technology stack—including models, hardware, software, and standards. Accordingly, while recognizing that decisions on whether and how to release a model are ultimately for developers, the Action Plan includes several measures aimed at increasing open innovation and implementation, including convening stakeholders to help small and medium-sized businesses adopt open models. The government’s procurement agency is also facilitating adoption of Llama models by federal departments and agencies. However, there is no indication as yet that the Action Plan has prompted a shift in the strategies of leading US developers.

Other countries are trying to carve out their space in the open AI landscape

In Europe, French company Mistral was an early leader in open AI models but has since lost ground to Chinese competitors—the share of global finetunes and derivatives based on EU models dropped from 37% in November 2023 to 6% in December 2025. Nevertheless, EU policymakers continue to back open European models: EuroHPC has granted the OpenEuroLLM project 10 million GPU hours on the continent’s most powerful supercomputers, and a European Open Digital Ecosystem Strategy is being developed to position open source as “crucial to EU technological sovereignty, security and competitiveness.”3

At the same time, the EU AI Act reflects nuanced considerations around open-weight model safety. It exempts most open-source general-purpose AI (GPAI) models from documentation requirements, recognizing both innovation benefits and the inherent transparency of open releases. However, models above a certain capability threshold must comply with all obligations for GPAI models with systemic risk, regardless of licensing terms. While Meta refused to sign the GPAI Code of Practice, other developers are making full compliance part of their edge. Switzerland’s Apertus, the country’s first large-scale open multilingual model suite, was designed with data compliance in mind while approaching state-of-the-art results on multilingual benchmarks.

Further afield, developers in many Global Majority countries, such as India and Vietnam, have prioritized adapting existing open models with local language data. In multilateral AI policy debates, increasing access to AI models, data, and infrastructure—and the benefits that derive from them—continues to be a priority topic for lower- and middle-income countries. Meanwhile, Gulf states benefiting from significant energy and capital resources are combining end-to-end training of locally tailored models (such as the Arabic-centric Jais 2) with sovereign deployment of foreign open-weight models (such as Saudi company Humain’s collaboration with Groq on high-speed inference of open models from OpenAI).

A common agenda for responsible open AI

While this (non-comprehensive) survey demonstrates clear differences in capabilities and strategic priorities across regions, there is broad consensus that for the vast majority of AI models, the benefits of openness—innovation, diffusion, and inclusion—outweigh the risks. Conversely, few would argue that future models with the potential to enable large-scale harm, such as the design of weapons of mass destruction, should be released without restriction.

Key questions for the international community are therefore:

- Can we build technical safeguards that reliably resist malicious finetuning and reduce the risks of large-scale harm from capable open AI models? Emerging research directions include training algorithms designed to make models resist tampering and filtering out potentially harmful knowledge from training data.4 Developing more robust frameworks for evaluating durable safeguards will be crucial for measuring progress.5

- Given that reliable safeguards do not currently exist—and may never be fully achieved—what governance solutions or access restrictions are needed? At what points along the capability spectrum should they be introduced? Possible approaches include staged release: gradually rolling out access to more model artifacts as confidence in risk management increases and/or the capability frontier advances. Another is managed access, where different users are given differentiated access permissions based on how trusted they are. In determining which models should be subject to access restrictions, training compute alone is unlikely to be a sufficient indicator of risk. Relatively small open-weight models could still pose significant dual-use risks if trained on data from higher-risk domains such as biology.

- How should liability be assigned for incidents involving open models? There is increasing interest in reforming liability regimes to incentivize suitable precautions from AI developers and provide redress for harms to third parties as well as users. As these policy debates evolve, a major question will be how to treat open model developers, who have limited ability to monitor and restrict downstream use after making model weights available.6

Progress on these questions requires more research and international dialogue. Continued exchanges among developers, policymakers, and researchers are needed, including in forums such as the UN Global Dialogue on AI Governance. These will help surface lessons and trade-offs, clarify roles and responsibilities, and build a shared understanding of best practice.

- Similarly, the technical report for DeepSeek-V3.2 stated a plan to scale up pretraining compute.

- Chinese discourse tends not to distinguish between open-weight and open-source models, instead using the latter as a catchall term.

- For reference, the training of DeepSeek-V3 took ~2.8m GPU hours.

- See Open Technical Problems in Open-Weight AI Model Risk Management for an overview of existing technical work in open-weight model risk management and outstanding challenges.

- As researchers from Princeton and Google have shown, evaluating methods for safeguarding open-weight models is challenging. Different implementation details can yield different evaluation results and side effects of a defense method might be missed by the evaluation.

- As an early intervention in this debate, the European Union’s revised Product Liability Directive (2024) explicitly brings software within scope, while excluding free and open-source software developed or supplied on a non-commercial basis.